“What a Journey”: Four Brunonian pitchers’ pursuit of a place in Major League Baseball

11/25/2025

by: Linus Lawrence '25

On March 20, 2022, the Brown baseball team played its first home games since May 6, 2019. After two covid-canceled seasons, a ten-game road trip, and innumerable hours of practice, a doubleheader against Northeastern and Holy Cross finally marked the Bears’ long-awaited return to Attanasio Family Field.

Over 200 fans were in attendance that day, eager to watch their beloved student-athletes return to action. As it turns out, they may have been watching future major leaguers on the mound.

In the first game, Bobby Olsen ’23 — a junior from Powdersville, South Carolina, making just his third collegiate start — tossed six innings of one-run ball, striking out seven and flashing superb stuff.

In the afternoon contest, a trio of Bears relievers took the bump in the late innings.

The first was Charlie Beilenson ’22, a right-handed senior from Los Angeles. Beilenson hadn’t found much success thus far with the Bears, but he was brimming with striking levels of confidence and competitiveness.

The second was Rhode Island native Zach Fogell ’22, a 5’11 southpaw who spent the canceled seasons rehabbing from Tommy John surgery — a process more complicated than planned as a result of the pandemic.

The third was Jack Seppings ’25.5, a freshman from Newnan, Georgia with undeniable potential and an unhittable slider that Bears catcher Jacob Burley ’24 called an “alien pitch.”

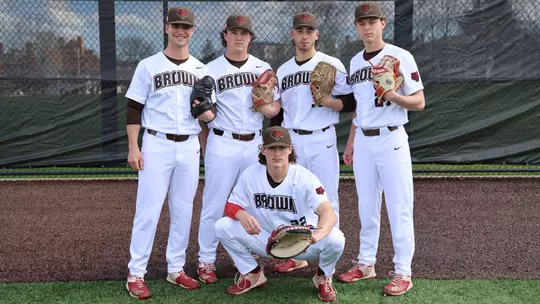

At the time, Beilenson, Fogell, Seppings and Olsen were bonded by the “B” on their cap and the “P” next to their name in the lineup. Now, they share something else in common: all four former Bears just finished the 2025 season as minor league baseball players.

Whether hearing their names called on draft day or a bullpen phone, battling through torn ligaments or mental blocks, meeting their heroes or rising to meet the challenges of a new stage, these players’ journeys from amateurs to pros are the product of remarkable ability, transformative adversity, and tireless hard work. After twelve MLB teams strove toward the ultimate goal of winning a World Series this October, this is the story of four Brunonians striving for years to earn a spot in the show — and now potentially on the verge of getting it.

“Oh my gosh, maybe I can”

In the early 20th century, Brown University was something of a breeding ground for professional baseball players. But since 2000, only 14 Bears have been drafted. The most recent Brown graduate to reach the majors was shortstop Bill Almon, a first overall pick by the San Diego Padres in the 1974 MLB Draft, and the most recent to reach Triple-A was shortstop Todd Carey in 1997.

“I think it’s naive for anybody to show up in Providence and be like, ‘okay, I need to be focused on how to become a pro,” said Mark Sluys ’19, a former catcher and current Area Supervisor in the Pittsburgh Pirates’ amateur scouting department.

For Charlie Beilenson, academics were always the focus. He traveled across the country as a high schooler, pitching in showcases with the goal of landing a spot at a top academic, Division III program.

“My whole recruitment process was kind of trying to use baseball to get into the best school that I could,” he recalled. “I never really saw myself as a D1 baseball player.”

Even after Brown recruiters saw him pitch at a tournament in Arizona, even after he got word in the middle of a calculus class that his “number one school” wanted him on their team, and even after he became the D1 pitcher he didn’t envision himself as, Beilenson’s number-one priority remained academics. In his view, this dynamic wasn’t a hindrance to his success as a baseball player, but a contributing factor.

“Looking back, all that discipline on the academic side allowed me to pursue baseball with no fear,” Beilenson said, characterizing it as a “playing with house money” mentality. “If it doesn’t work out in the end, I’ve done everything I can to set myself up well on the other side.”

Perhaps it’s that attitude which imbued Beilenson with an unmistakable air of confidence, even while struggling to find results at times in his early days with the Bears.

“He still went into every at-bat thinking — or in his head, knowing — that he was gonna get that batter out,” Burley said of Beilenson’s approach. “It’s not performative at all. He really believes that he’s gonna come in there and get you out.”

“Sometimes he likes to talk a little crap to the hitters, too,” Fogell said of his former bullpen-mate, calling Beilenson “the quirkiest kid I’ve ever met,” a “great teammate,” and a “great competitor.”

Like Beilenson, Fogell arrived at Brown in the fall of 2018, calling it “the best of both worlds being able to play Division I baseball while getting an Ivy League education.” Unlike Beilenson, Fogell got to Providence by moving just about a dozen miles south from Cumberland.

The local left-hander quickly cemented himself as one of the most trusted arms in the Bears’ relief corps, throwing 21 innings across 15 appearances (the third-most on the team) in his rookie season. The last of those appearances came on May 4, 2019, facing Harvard at home. Entering with one out in the ninth inning as the Bears looked to seal a win, Fogell issued an uncharacteristic five-pitch walk, marking just his fourth free pass in Ivy Play. The coaching staff noticed Fogell shaking his hand on the mound in apparent discomfort, and removed him out of caution.

“I’m really bad at taking myself out of ballgames,” Fogell said. “That’s just stupidness, looking back. But in that moment, I’m not taking myself out of the game. I want the ball in my hand.”

Fogell was initially diagnosed with a minor flexor injury in his elbow, and was back on the mound for his first summer ball outing in the New England Collegiate Baseball League on June 8. The next morning, Fogell woke up unable to move his arm. After trying to pitch through what appeared to be yet another flexor injury, Fogell finally underwent Tommy John surgery in September 2019.

While the difficulty note-taking and typing for classwork might have been anticipated, Fogell couldn’t have predicted the twist his road to recovery would take. Just as his throwing programs were beginning to ramp up in the spring, physical therapy and rehab appointments suddenly went virtual due to Covid.

“I remember being in my basement with a butter knife, scraping my scar to try to get rid of scar tissue,” Fogell said. “That’s what my PT was telling me to do, cuz I couldn’t go in and see him.”

Fogell had been working toward the goal of returning in a 2021 season that no longer existed. By the time the long-awaited day arrived in Memphis on February 25, 2022, nerves accompanied it, prompting Fogell to begin warming up an hour and a half before first pitch and draw questions from his pitching coach Christopher Tilton.

“It was two and a half years since I stepped on a baseball field,” Fogell recalled. “I was just so jittery and so anxious to get going.”

Fogell felt “rusty” at first, but ended up putting together an impressive senior season, striking out 46 batters in 39 innings pitched. “The first year back in 2022 was a great year of just learning how to pitch again, and learning what my body needs to progress,” Fogell said.

“He needed that year to kind of get his bearings underneath him,” Burley said. “He was always that good. He just finally got comfortable again and healthy again.”

While Fogell’s teammates weren’t sporting a reconstructed ulnar-collateral ligament, other Bears emerged from the multi-year drought with matured bodies, skills, and mindsets. For Olsen, now an upperclassman without a game of Ivy Play under his belt after Covid unexpectedly interrupted what he called a “whirlwind” freshman spring, the time away from the diamond transformed into an opportunity.

“I think maybe it was kind of a blessing in disguise,” Olsen said. “I would have loved to have been on campus and competing and playing games, but those two years really gave me some time to focus in and hone in on my craft.”

Olsen’s junior year didn’t yield the results he wanted, but it provided insight into what he needed to work on. After an offseason of focused training, Olsen posted an 11.9 K/9 rate his senior year behind a mid-90s fastball and what Burley, who later played at Wake Forest University, called “one of the best breaking balls” he’s ever seen.

When Covid canceled Beilenson’s sophomore and junior seasons, he wasn’t particularly concerned about the ramifications for a potential professional baseball career that he didn’t think possible at the time. It was upon his return to the diamond in 2022 that Beilenson began to imagine playing baseball beyond Brown, no matter the end result.

“What happened my senior year really helped me find the love for the game again,” Beilenson explained. “It was the first time being back in two years, playing on the field with the guys, and it’s like, ‘wow, this is just the most fun thing ever. I have to do this for as long as possible.”

With the help of the NCAA’s decision to allow extra years of eligibility in the wake of the pandemic, Beilenson, Olsen and Fogell each decided to continue their collegiate baseball journeys beyond Brown.

In his first season at Duke, Beilenson “put on a ton of muscle” to achieve a velocity bump while “tinkering with a bunch of new stuff,” adding to his pitch repertoire and altering his existing pitch shapes. In 2024, his tinkering paid off to the tune of an outstanding 2.01 earned run average — the second-best in Division I baseball, just ahead of the Toronto Blue Jays rising superstar Trey Yesavage — and 92 strikeouts in 62.2 innings pitched. Beilenson had become, in Burley’s eyes, “the best reliever in the country.”

“It was kind of just a slow progression of, ‘Oh my gosh, maybe I can. Oh my gosh, maybe I can,’” Beilenson said of his collegiate trajectory. “It was probably five, six years of slowly but surely dialing it in. Maybe a little slower than some other people learned to figure it out, but in the end it worked out.”

With his eyes on pro ball, Olsen spent a season at University of Nebraska-Lincoln before transferring once again to Villanova University.

“I absolutely loved it there,” Olsen said, explaining that Villanova’s coaches “really helped me figure out who I was as a pitcher.”

“He’d always been so talented,” Burley said of Olsen. “He always had the potential. He always had the stuff. It was always right there in front of him. For him to finally at Villanova this past year kind of put it together, and have a season worthy of someone signing him, it’s great to see that finally come to fruition.”

Fogell stayed in New England, going to University of Connecticut for a single dominant season. As a Husky in 2023, Fogell struck out 60 batters in 47.2 innings pitched, posted a 1.89 ERA, and finished with an 8-0 record.

Before the opening game of a series at St. John’s University, UConn pitching coach Joshua MacDonald approached Fogell to inform him that two scouts in the crowd were there to watch him. “As a small town kid from Rhode Island who was undersized and doubted, it was a great feeling to see that people are recognizing the success and what I could do at the next level,” Fogell said.

One week later, Fogell was on the plane ride home after an especially impressive series at Xavier University when MacDonald asked if he had an agent. Fogell hadn’t heard any word that he might be drafted, asking, “Why would I have an agent?”

“He was like, ‘I’m gonna get you one,’” Fogell recalled. “That was kind of the first moment where I was like, holy —, this could actually happen.”

“In a matter of ten minutes”

As his stellar spring at UConn continued, Fogell suddenly began receiving questionnaires from MLB organizations — a process Beilenson was also experiencing at Duke.

“My fifth year, the Mariners were the only team that reached out to me,” Beilenson said. The sixth year, “I think I heard from probably all thirty teams.”

As the 2023 MLB Draft approached, Fogell was informed he could expect to be drafted between the 10th and 15th rounds, as well as which team appeared most likely to select him.

“I actually thought I was gonna get drafted by the Yankees,” Fogell recalled. “My parents were like, ‘we’re not rooting for the Yankees,’ joking around and stuff.”

The fifteenth round came and went as Fogell’s spirits fell. In the 17th round, he got a text from former Brown teammate Mark Sluys. Four years earlier, Sluys had been the Bears’ catcher and captain for Fogell’s freshman season, with Fogell describing him as “one of those guys you kind of looked up to.” In 2023, he was an Amateur Scouting Assistant for the Boston Red Sox.

Sluys was watching while Boston’s board of late-round pitching targets, a group including Fogell, diminished as other organizations made their selections. One round later, Sluys informed Fogell that the Red Sox would be drafting him.

“It went from the worst day of my life to the best day of my life in a matter of ten minutes,” Fogell said.

“It’s obviously something that’s pretty unique,” Sluys said of helping draft his former batterymate. “It was fun to be able to have it work out the way it did.”

The following year, Sluys reached out to Beilenson ahead of the 2024 MLB Draft — only this time as a courtesy, to convey that he shouldn’t expect the Red Sox to select him.

Beilenson was unsure when, if at all, he would be drafted. As the fifth round approached, he got a call from his agent telling him to watch the MLB Network livestream. “There’s no way,” Beilenson remembered thinking. “I had absolutely no thought that I would go as early as I did.”

With the 18th pick in the fifth round, Beilenson was selected by the Seattle Mariners — the only team that had contacted him prior to his phenomenal final year of collegiate ball.

“It was unreal,” Beilenson said. “Heart-pounding. Kind of happened so fast that it was all a blur. Kind of cliché, but absolutely true.”

The heart-pounding experience of seeing your name during the draft isn’t the only way for college prospects to find a home in pro ball. All 30 MLB organizations typically sign a handful of undrafted free agents to join their draft class each summer.

Nineteen-year-old Jack Seppings arrived on College Hill in the fall of 2021. Like many Brown student-athletes, he was searching for a school that allowed him to “marry academics and baseball,” making the decision to become a Bear a “no-brainer” for him. Like many Brown student-athletes, he also remembers his rookie season for its learning points. In Seppings’ collegiate debut, he threw two perfect innings while racking up five strikeouts. In his next outing at Gardner-Webb, he allowed five runs in one inning.

“I was on top of the world, and then was dealing with something that was a tough pill to swallow, losing a game for your team,” Seppings said. “That was something that always kind of sat with me, and taught me to stay more even-keel.”

Even as a freshman, Seppings displayed exceptional stuff, including a slider which — according to his catcher Burley — could be thrown “ten times in a row and no one would hit it.”

“You saw that potential immediately,” Burley explained. “He had the ability, he had the talent, he had the work ethic from the get-go.”

“I kind of always knew he was gonna eventually play professional baseball,” Burley said.

On April 5, 2022, Seppings got the final three outs of the first no-hitter in program history. Seppings, Beilenson, and Olsen accounted for eight of the nine no-hit innings against Holy Cross, with Paxton Meyers ’24 delivering the other. At the time, Beilenson called it “the best outing of my career here.”

After an injury cut his rookie year short, Seppings emerged from the long offseason feeling “like a completely different pitcher. I put on 15-20 pounds, was throwing a lot harder, and was able to kind of put myself in a position to make a little more noise,” Seppings said.

Seppings delivered a fantastic sophomore season, leading the Bears in relief innings and putting together a stretch of 12.1 scoreless innings pitched in April. “It’s all about stacking the good days on top of the good days, and then not stacking bad days,” Seppings said, “and I think I learned that a lot my sophomore year.”

Back in March, Seppings had briefly separated from his fellow Brunonians to participate in Team Great Britain’s minicamp for the World Baseball Classic, eventually being named to the team’s taxi squad. While in minicamp in Arizona, Seppings threw a scoreless inning against the Milwaukee Brewers in an exhibition game.

Though his junior year didn’t yield the results he had hoped for, Seppings went on to thrive at the Cape Cod Baseball League for a second consecutive summer. In 2023, he felt the CCBL had put him “on the map” for scouts, while in 2024, the CCBL “kind of solidified that (junior) year doesn’t define me.”

Seppings traveled home to be with his family for the 2024 draft. When the final round concluded, he was disappointed not to have heard his name called.

“I obviously felt like I did a good job my sophomore year, or even earlier in the Cape right before the draft, my numbers were good and I felt like I’d bounced back,” Seppings said. “But that’s how it goes. Sometimes it doesn’t work out, and it all worked out in the end.”

After returning to Cape Cod and throwing one more outing, Seppings received a contract offer from the Brewers — the same team he’d faced with Great Britain in Arizona a year earlier.

As the final day of the 2025 Draft unfolded, Olsen was stopping in Lincoln to visit old friends and family from his days as a Cornhusker. He was with Charlie Colón, an alum of the University’s baseball program and Olsen’s former boss at a local Chick-fil-A, when the draft finished. Mere minutes later, Olsen received a phone call from his agent asking if he’d like to be a member of the St. Louis Cardinals. Within a few days, he was on a flight to the Cardinals’ complex in Jupiter, completing an orientation, physicals, and eventually signing his contract.

“Everybody was super excited,” Olsen said, “especially your immediate family that were there with you your whole life, since you were five years old playing baseball and going to travel tournaments. They’ve been there through everything with you. To finally achieve that, it’s unbelievable."

“With a little bit of development”

The life of a minor league baseball player consists of six baseball games a week, with six to twelve hours of travel every other week, for almost six consecutive months.

“Every day your body hurts,” Fogell said. “It doesn’t matter if you’ve had three days of rest or one day of rest from pitching, or if you’re a position player and you got your off day yesterday. Your body’s still in pain. It’s just a very demanding season.”

Still, with the heightened workload, stakes and competition, one element remains fundamentally the same: the game.

“You’re at the next level, you got the uniform on,” Olsen said, “but nothing changes. It’s the same mound. It’s the same distance…You’re the same pitcher that you’ve been, and you don’t want to change that cuz it’s what got you there.”

That’s not to say pitchers don’t evolve in meaningful ways over the course of their time in the minor leagues, whether adjusting their mechanics, approach or pitch arsenal. These adjustments are often made using the help of new technology which has rapidly spread throughout the sport in recent years. Fogell receives a report after every outing with his pitch metrics, while Olsen credits the combination of Edgertronic cameras and Trackman data with helping him “lock in a grip, or a certain spin you’re trying to chase.”

Early in their respective minor league journeys, Fogell and Seppings both learned a new pitch: the cutter. For Seppings, the decision to add a cutter to his repertoire came out of a mutual desire between him and his coaches. For Fogell, the recommendation came when the Red Sox’ coaching staff noted the need for a pitch with less dramatic movement compared to his sweeper and change-up.

“At first, I hated it,” Fogell said. “I couldn’t throw it for a strike. I couldn't get it to the other side of the plate.”

With the help of pitching coach Sean Isaac at the Arizona Fall League last offseason, Fogell broke through a “mental gap” and began to utilize the cutter as an effective weapon.

“I was starting to get a lot of swing and miss on it, because it’s just so deceptive from the fastball,” Fogell said. “It turned out to be one of my favorite pitches to throw…It’s funny how some things work with a little bit of development.”

Seppings now views the cutter as his best pitch, explaining that throwing the pitch early in counts allows him to “diagnose” how to approach an at-bat. Being able to sequence pitches by “reading hitter swings” is an ability which Seppings feels he’s learned since joining the Brewers organization — especially when it comes to the cutter.

“I had a lot of questions about when to use it,” Seppings said. “What kind of swings would it do good attacking with, and what kind of swings should I probably avoid using the cutter and (use) more fastballs and something slower than the cutter?”

Beilenson’s coaches have preached a particular philosophy of pitching, encouraging him to “dominate the zone” and be aggressive, especially in 0-0 and 1-1 counts.

“The entire Mariners philosophy is basically throw the ball down the middle and see what happens, and if your pitches move enough they should get hitters out,” Beilenson explained. “As you get older, and you can kind of hit your spots a little better, then you start making those adjustments of aim smaller, miss smaller.”

The strategy has had a visible impact on Beilenson’s results, with his walk rate falling from 2.6 walks per nine innings in his final year at Duke to 1.3 BB/9 in the second-half this season. It’s also reflected in the Mariners’ success at the major league level. Across the past three seasons, Seattle leads the majors with a 65.9% strike rate and 2.6 BB/9 rate, as well as ranking second with a 3.70 ERA.

“In some organizations, you might move because your stuff is so good,” Beilenson said. “For us, it’s like, ‘We need to be seeing strikes out of you and then you can move.’ Dominate the zone is the priority.”

Certain organizations emphasize different abilities and approaches, which also affects what traits they value in a potential draftee. As Sluys put it, organizations look through “different lenses.”

“Zach’s fastball always had life, always had some carry, and Charlie has a natural ability to spin the baseball,” Sluys said. “We spent more time worrying about fastball characteristics in Boston with the idea that we have better luck adding breaking balls and off-speed pitches. Fastball shape is a hard thing to develop. It’s more of an innate trait.”

An organization’s culture can permeate a player’s development beyond just shaping their approach on the mound.

One night while Olsen’s father and uncle were visiting him near the Cardinals’ Single-A complex, the trio ended up having an impromptu hotel dinner with two-time All-Star and World Series Champion Jason Isringhausen.

“There is a long-standing history and legacy of what it means to be a Cardinal,” Olsen said, “and I think one of the biggest things that helps you realize that is day to day, you’ll see a guy walking through the clubhouse or through the facility, and you’re like, ‘holy —, that’s a Cardinals Hall of Famer.’”

Fogell has met several Boston legends, including his favorite player and fellow left-hander Jon Lester, who came by to give the minor league pitchers a talk about glove tipping. Fogell wore Lester’s number 31 on all his childhood baseball teams, up through his freshman year at Brown.

Fogell has also had the opportunity to pitch in a handful of Red Sox spring training games. During his first spring training appearance on February 23, 2024, Fogell entered a bases loaded, two-out jam.

“I hear the bullpen phone ring, and I’m like, ‘No way it’s me.’ And then it ended up being my name,” Fogell said. “At that moment, it was just an adrenaline rush.”

The southpaw claims he struggled to process his surroundings during the “surreal” experience. Back in the dugout after inducing a first-pitch lineout, he asked his friend Niko Kavadas when he was set to enter the game. Kavadas had in fact been playing first base, and had hit Fogell on the back when he arrived at the mound.

“Cora is handing you the ball, Jason Varitek’s sitting there as the bench coach,” Fogell recalled. “Growing up being a Red Sox fan, it’s kind of a crazy moment to have.”

“I got an ESPN notification that Zach Fogell got the (win) in a Red Sox big league spring training game,” Burley recalled, referencing Fogell’s appearance against the Phillies three days later. “I’m like, ‘holy —.’”

Beilenson’s first spring training outing came this February against a Brewers lineup which would go on to score the third-most runs in baseball this past season. The third batter he faced, Jake Bauers, lined the ball off the ground straight into Beilenson’s hamstring. The pitcher picked up the ball and fired it over first baseman Rowdy Tellez’s head, allowing two runs to score. When asked if there was any video of the play, Beilenson responded: “Gosh, I hope not.”

At that point, Beilenson’s sole experience with the Mariners had come at Low-A — the lowest of four primary levels in the minor league system, followed by High-A, Double-A, and Triple-A before the major leagues. Fogell and Seppings are both currently in High-A, while Olsen, having been drafted this summer, has just gotten his feet wet in Low-A.

At the start of the 2025 season, Beilenson was assigned to the Mariners’ High-A affiliate in Everett, Washington, where he had success for two and a half months. One day in mid-June, while riding home on the team bus, Beilenson got a text from the Mariners’ Double-A clubhouse manager asking for his uniform and hat sizes, leading him to realize a promotion might be in store.

The following day, Beilenson was woken up to a call from his High-A manager. “You’re still sleeping?” Beilenson recalled hearing over the phone. “You could have missed your call to Double-A!”

“Between the ears”

For those already climbing the minor league ladder, the rise in competition has appeared most noticeable in hitters’ increased patience and intention at the plate.

“Every level you go up, it’s the same type of players with a better mental approach,” Fogell said. “What I noticed from Low-A to High-A right away was these hitters are less aggressive, they don’t chase as much, and they’re looking for their pitch…Chases get smaller and smaller, the zone gets a little bit smaller, but the competition’s mostly the same.”

Double-A players “just aren’t chasing the pitches that some of the High-A guys were chasing, and definitely the Low-A guys,” Beilenson said. “It’s just consistency and discipline across the board. A lot of the talent is the same, but just the ability to do it day in and day out in Double-A is probably the most noticeable thing.”

Having the right mentality can be the key to advancing through the minor leagues, but overly dwelling on the topic of promotions or prospect rankings can ultimately prove a distraction.

“The toughest part I think is when you have success, and you feel like you deserve a promotion, sometimes you don’t get it,” Fogell said. “Sometimes you get promoted for a day or two to fill in a spot they need, and then you get sent back down. It’s a very grueling, demanding process that you have to do. It’s definitely tough to stay in the right mindset to be able to compete every time you go out there.”

It’s the mental side of pitching where all four former Bears cited Brown’s lasting impact, recalling a variety of cues and catchphrases shared by the program’s coaches to help them stay in a good headspace on the mound.

For Seppings, a motto that has stuck with him is to “speak to yourself more than you listen to yourself.” If he listens to his own head after throwing a ball on the first pitch of an at-bat, he’ll hear it say “dang, I missed,” as he put it. Instead, if he focuses on speaking to himself, he can keep a positive approach. “A lot of baseball is obviously between the ears,” Seppings remarked.

“He’s a very smart kid,” Burley said of Seppings. “He’s one of those guys that needs to almost shut off his brain more than he needs to turn it on.”

“You have all these things in your head, no matter who you are,” Seppings said. “It’s human. No matter if you’re pitching (for) a month and you haven’t given up a hit, or you’re just in the middle of a tough stretch…We learned so many routines that I still use today too, without even thinking about it, that came from my time at Brown.”

For Fogell, another motto is “bad pitch, good pitch.” If he throws a bad pitch, he tells himself to "reset, take a deep breath, get back on the mound and throw a good one here,” he said.

“Baseball’s such a mental sport,” Fogell explained. “If you have a bad mindset on that mound, you’re not gonna succeed. That’s something I’ve learned through failures and success.”

“A lot of the mental training that we did with Coach Tilton helped a lot,” Olsen said. “Just routines, how to sleep better, your breathing on the mound, staying present, staying focused — that all really helps me, and I think even today I use that when I pitch.”

Beyond the baseball field, some cited adversity during their time at Brown as another source of mental training, whether adjusting to covid or managing academic workload.

“The academic side is very challenging and mentally hard. When it comes to baseball, half the battle is the mental side,” Beilenson said. “So I figured if I can get through going to an Ivy League school, the mental battle here should not be the issue.”

Some have even found applications for their degrees as minor leaguers. Fogell concentrated in Business, Entrepreneurship, and Organizations, which has since been phased out by the University. In addition to providing enhanced collaboration skills, Fogell felt the concentration helped him feel confident comprehending the financial side of baseball.

“Whether you like it or not, professional baseball is a business,” he said. “You have to understand the ins and outs of how arbitration works and contracts work. With that understanding…it feels like you’re more prepared for certain situations, and it helps ease the pressure of trying to perform every day as you’re trying to compete for a position.”

“It’s hard not to grow there,” Sluys said of Brown. “I learned just as much in the classroom as I did talking with teammates or classmates. You hear a lot of different perspectives and really different processes of thinking.”

Olsen concentrated in International and Public Affairs, taking four semesters of Spanish courses which have allowed him to bond with Latino teammates and coaches on a more meaningful level, bridging the difficult “communication barrier” that he explained often exists in clubhouses.

“Although I can’t speak it as well as they do, I can understand and communicate with them, which is pretty fun and I’m pretty grateful for,” Olsen said. “Even like day-to-day conversations, just joking around, having a good time, it’s nice to kind of bridge that gap,” Olsen said.

After finishing his first full season of minor league ball on September 7, Seppings is now back in Providence for one last semester to earn his Applied Math-Economics degree, which he enjoys keeping in a separate headspace from athletic pursuits. Hoping to build off his 3.82 ERA in 20 appearances at High-A Wisconsin, Seppings looks forward to “hitting the weight room pretty hard,” working on his command, and learning a sinker to complement his cutter this offseason.

Before arriving at his first spring training, Olsen will strive to “build off the success” of his early minor league career by adding more velocity, while Beilenson similarly has his sights set on “learning how to throw harder.” The 25-year-old Beilenson has played his house money to the brink of the major leagues, currently ranked the No. 26 prospect in the Mariners organization by MLB.com.

It’s “not anything I ever expected to be on one of those lists,” Beilenson said. “To be there right now is pretty crazy, pretty awesome, but not something I try to think about too often. I don’t want to let it be a distraction.”

Fogell, meanwhile, will spend the offseason recovering from his second Tommy John surgery — one performed by the same surgeon, Dr. Luke Oh, almost six years after his first as a freshman at Brown. This time, rather than recovering as a student in the heart of the pandemic, he’s a professional with the support system of a major league organization behind him, as well as the benefit of six years of medical advancement.

“There’s a lot more research that’s been done, and it’s a lot more successful now obviously,” Fogell said. “The knowledge increase is a lot more comforting…It’s just a very seamless process, it feels like.”

Fogell felt on top of his game in the week leading up to the injury, calling it “probably the best I’ve ever pitched.” Like six years ago against Harvard, Fogell didn’t take himself out of the game on May 24 at Bowling Green, throwing 21 pitches with a torn UCL as his season ERA shot from 1.65 to 3.24. The southpaw won’t throw a baseball until January. He hopes to return before the conclusion of the 2026 season, and if he does, he has another goal in mind: earning a promotion to Double-A.

For now, Fogell is back home in Cumberland, twenty minutes from where a new generation of Brunonians prepare for the season ahead — and with it, the next step of their unique, unpredictable baseball journeys.

“That’s the part that I look back on,” Burley reflected. “Man, what a journey Zach Fogell had. What a journey Charlie Beilenson had…I had a first-hand experience in all their careers, and it just makes me happy knowing those journeys that they’ve been on that they are where they are today, and they have the opportunity to make the big leagues.”

The 2022 season marked the only time that Beilenson, Fogell, Seppings and Olsen overlapped in a Bears uniform.

But for those who shared a locker room, a campus, and countless lifelong memories with those four players, perhaps that ’22 team gets some spiritual opportunity to live on — at least as long as the quartet’s baseball careers continue. As Burley explained, the accomplishment sparks a “sense of pride,” not only as a catcher who worked to help them develop on the field, but as a friend and teammate on a close-knit club.

“Just the camaraderie we had, we all were great friends,” Burley reminisced. “We all wanted each other to succeed, and for the most part everyone on that team would love to be in these four guys’ shoes playing in the minor leagues…We put in a lot of hard work, and if no one from those teams had gotten a chance, that would have been awful.”

“Obviously we would have wanted to win more,” Sluys said, “but it never takes away from the pride that I have for the University and for the baseball program. You root for these guys. You want them to pitch in the big leagues. You want them to have as much success as they can because they’re good human beings, and also because (that) can only help the program, right?”

“I get a lot of people asking me, ‘wow, you’re so good, do you wish you could have gone somewhere else?’” Beilenson said. “I’m like, ‘absolutely not.’ Those were my favorite years. I would take my teams, my classmates, the friends I made there over going to any other school for any other reason.”

“Providence, Rhode Island, I’ll always love,” Beilenson added. “Go Bruno, baby.”